A fighter is a flying machine designed to shoot

down enemy aircraft, besides performing many other ground attack roles. Depending on the threat to be countered, the

operating environment and the weapons available, capabilities of a fighter vary

widely. Trade-offs are made in several

areas, the more prominent ones being performance and manoeuvrability. Each fighter is, therefore, a compromise, but

with certain qualities emphasised in order to best fulfil the primary task for

which it has been designed.

Aircraft Performance includes

parameters like rate of climb, ceiling, acceleration and speed which play a

significant part in the interception of an adversary; the latter two parameters

can also help in rapidly extricating out of a thorny situation. As would be expected, unbeatable aircraft

performance is dependent on good design, and availability of excess

energy. Thrust produced by the engine can be a convenient

index of available energy; however, when an aircraft is considered as a mass

acting under the force of gravity, a simple reading of engine thrust values can

be misleading. ‘Thrust-to-Weight (T-W)

ratio’ is the factor that helps appraise aircraft performance in a correct

perspective. Besides enhancing basic performance

parameters, a high T-W ratio also helps sustain turn rates by countering the

effects of drag induced during manoeuvring flight.

Higher thrust is, of course,

produced by paying the penalty of higher fuel consumption. Sufficient on-board fuel quantity can thus be

seen as an important factor if aircraft performance is to be fully

exploited. ‘Fuel fraction’ is a term

used to denote the internal fuel as a fraction of aircraft weight in the clean

configuration. It gives an idea of the

staying power in a dogfight, assuming that fuel consumption rates of different turbojet

engines are largely similar. A fuel fraction of less than .25 for

afterburning turbojet fighters and .20 for non-afterburning ones is considered

inadequate.

Manoeuvrability, or the ability

to out-turn an opponent, is an important attribute of a fighter. Turning is measured both in terms of radius

of turn as well as rate of turn. A good

radius of turn is a ‘nice to have’ feature, but an attacker rarely needs to

turn as tightly as his adversary to maintain a favourable position in a stern

attack, unless at very close ranges. A defender, on the other hand, needs to

swing his tail away from an attacker’s flight path as fast as possible by

generating a high rate of turn. Thus in

a turning fight, rate of turn is of greater significance than radius of turn.

Turning ability is dependent on

wing design, and the easiest understood feature is ‘wing loading’ or the weight

of the aircraft per unit area of the wing (which is the source of most of the

aircraft lift). During a turn, when

banked flight tilts the lift vector away from the normal, and drag wrecks

whatever remains of the angled lift, a low wing loading comes in handy to help

balance the essential lift-weight equation.

Low wing loading is thus advantageous to an aircraft turning for a

smaller radius, as well as a higher rate of turn, at any given speed. At very low speeds, however, when an aircraft

is on the verge of stalling, devices like slats and flaps preserve/generate

much needed lift; in such speed regimes low wing loading does not help matters

much.

Creating lift in an aircraft incurs

an unavoidable penalty in the form of induced drag. Aerodynamic efficiency is achieved by

designing a wing that produces maximum lift for the least drag. This is done by having a high ‘aspect ratio,’

which is the ratio of the square of the wingspan to the wing area. Since

induced drag happens to be inversely proportional to the aspect ratio, greater

the wingspan, lower the induced drag. A

high aspect ratio is thus an important factor in combat, as it helps in

sustaining turn rates. A good combination

for manoeuvrability would, thus, be low wing loading for enhanced turning

ability, along with a high aspect ratio to help sustain it. (High aspect ratio also improves endurance

and ceiling, and shortens take-off/landing distances.)

As fighters become faster,

their aspect ratios have to be reduced to minimise supersonic wave drag. This is done by presenting a smaller frontal

area to the supersonic airflow with the help of a smaller wingspan, besides

other profile streamlining techniques.

It can thus be seen that the conflicting requirements of high-speed pursuit

flight and subsonic manoeuvring flight have a bearing on the aspect ratio, and

compromises invariably result.

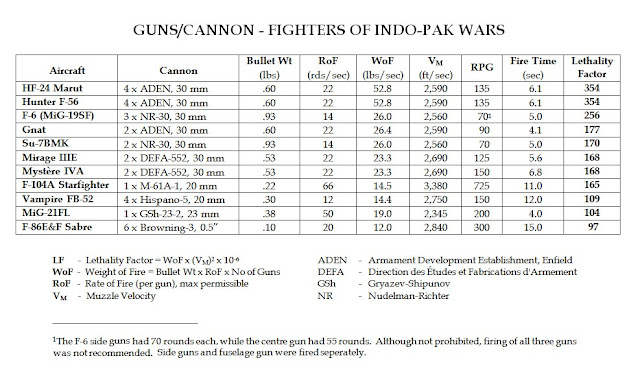

Fighters of Indo-Pak Wars

include some of the classics of jet age. The Sabre, Starfighter, Gnat and Hunter had earned reknown in

the Indo-Pak sub-continent due to the 1965 War. The later MiGs and Mirages are

no less celebrated, if for no other reason than their large production numbers,

and service in numerous air forces. Fighter

pilots who have flown these aircraft would swear that theirs was the best

fighter ever, with facts and figures to back up their claims. With due regard to their opinions, here is a

brief description of these fighters on the basis of some well recognised

criteria.

The F-6

was a Chinese copy of the MiG-19, the first supersonic fighter of the Soviet bloc.

It sported highly swept-back wings which, at 55 degrees, were considered

the right antidote to drag rise during transonic flight. Thick wings were the answer to the low lift generating ability of highly swept

wings, but drag rise due to the stubby profile did not help matters. Despite two powerful afterburning turbojet

engines which helped in initial acceleration, it could barely keep pace with subsonic

fighters at low altitude. Low wing loading coupled with a high aspect

ratio gave it excellent dogfighting abilities, though a poor fuel fraction limited its staying power in a dogfight. A pair of AIM-9B Sidewinder

missiles along with a set of three powerful 30-mm cannon were lethal weapons to

finish off an aerial target. The same cannon armed with armour-piercing

bullets, along with two rocket launchers having 8x57-mm rockets each, served a useful close air support

role.

The F-6

was a Chinese copy of the MiG-19, the first supersonic fighter of the Soviet bloc.

It sported highly swept-back wings which, at 55 degrees, were considered

the right antidote to drag rise during transonic flight. Thick wings were the answer to the low lift generating ability of highly swept

wings, but drag rise due to the stubby profile did not help matters. Despite two powerful afterburning turbojet

engines which helped in initial acceleration, it could barely keep pace with subsonic

fighters at low altitude. Low wing loading coupled with a high aspect

ratio gave it excellent dogfighting abilities, though a poor fuel fraction limited its staying power in a dogfight. A pair of AIM-9B Sidewinder

missiles along with a set of three powerful 30-mm cannon were lethal weapons to

finish off an aerial target. The same cannon armed with armour-piercing

bullets, along with two rocket launchers having 8x57-mm rockets each, served a useful close air support

role.

Though of Korean War vintage, the F-86F Sabre continued

to soldier on in many air forces, due largely to laurels earned during that

conflict. It was a good fighter from the

point of view of manoeuvrability, as the low wing loading and high aspect ratio

would suggest. Its low T-W ratio however

was no help in preventing speed from bleeding off in sustained combat. Paradoxically, this was an advantage that

turned the tables on many an opponent because of the Sabre’s superb low speed

handling, thanks to a fine slatted wing.

An excellent all-round view from the bubble canopy was a delight for the

Sabre pilots. The Sabre’s six 0.5" guns with

a total of 1,800 rounds provided enough firing time to target several aircraft,

as was demonstrated twice in the 1965 War. The Canadair CL-13 Sabre

Mk-6 (designated F-86E in the PAF, not to be confused with the regular North American

Aviation ‘E’ model) was better endowed than the ‘F’ model in terms of

T-W ratio, due to a more powerful engine.

Though of Korean War vintage, the F-86F Sabre continued

to soldier on in many air forces, due largely to laurels earned during that

conflict. It was a good fighter from the

point of view of manoeuvrability, as the low wing loading and high aspect ratio

would suggest. Its low T-W ratio however

was no help in preventing speed from bleeding off in sustained combat. Paradoxically, this was an advantage that

turned the tables on many an opponent because of the Sabre’s superb low speed

handling, thanks to a fine slatted wing.

An excellent all-round view from the bubble canopy was a delight for the

Sabre pilots. The Sabre’s six 0.5" guns with

a total of 1,800 rounds provided enough firing time to target several aircraft,

as was demonstrated twice in the 1965 War. The Canadair CL-13 Sabre

Mk-6 (designated F-86E in the PAF, not to be confused with the regular North American

Aviation ‘E’ model) was better endowed than the ‘F’ model in terms of

T-W ratio, due to a more powerful engine.

The F-6

was a Chinese copy of the MiG-19, the first supersonic fighter of the Soviet bloc.

It sported highly swept-back wings which, at 55 degrees, were considered

the right antidote to drag rise during transonic flight. Thick wings were the answer to the low lift generating ability of highly swept

wings, but drag rise due to the stubby profile did not help matters. Despite two powerful afterburning turbojet

engines which helped in initial acceleration, it could barely keep pace with subsonic

fighters at low altitude. Low wing loading coupled with a high aspect

ratio gave it excellent dogfighting abilities, though a poor fuel fraction limited its staying power in a dogfight. A pair of AIM-9B Sidewinder

missiles along with a set of three powerful 30-mm cannon were lethal weapons to

finish off an aerial target. The same cannon armed with armour-piercing

bullets, along with two rocket launchers having 8x57-mm rockets each, served a useful close air support

role.

The F-6

was a Chinese copy of the MiG-19, the first supersonic fighter of the Soviet bloc.

It sported highly swept-back wings which, at 55 degrees, were considered

the right antidote to drag rise during transonic flight. Thick wings were the answer to the low lift generating ability of highly swept

wings, but drag rise due to the stubby profile did not help matters. Despite two powerful afterburning turbojet

engines which helped in initial acceleration, it could barely keep pace with subsonic

fighters at low altitude. Low wing loading coupled with a high aspect

ratio gave it excellent dogfighting abilities, though a poor fuel fraction limited its staying power in a dogfight. A pair of AIM-9B Sidewinder

missiles along with a set of three powerful 30-mm cannon were lethal weapons to

finish off an aerial target. The same cannon armed with armour-piercing

bullets, along with two rocket launchers having 8x57-mm rockets each, served a useful close air support

role.  Though of Korean War vintage, the F-86F Sabre continued

to soldier on in many air forces, due largely to laurels earned during that

conflict. It was a good fighter from the

point of view of manoeuvrability, as the low wing loading and high aspect ratio

would suggest. Its low T-W ratio however

was no help in preventing speed from bleeding off in sustained combat. Paradoxically, this was an advantage that

turned the tables on many an opponent because of the Sabre’s superb low speed

handling, thanks to a fine slatted wing.

An excellent all-round view from the bubble canopy was a delight for the

Sabre pilots. The Sabre’s six 0.5" guns with

a total of 1,800 rounds provided enough firing time to target several aircraft,

as was demonstrated twice in the 1965 War. The Canadair CL-13 Sabre

Mk-6 (designated F-86E in the PAF, not to be confused with the regular North American

Aviation ‘E’ model) was better endowed than the ‘F’ model in terms of

T-W ratio, due to a more powerful engine.

Though of Korean War vintage, the F-86F Sabre continued

to soldier on in many air forces, due largely to laurels earned during that

conflict. It was a good fighter from the

point of view of manoeuvrability, as the low wing loading and high aspect ratio

would suggest. Its low T-W ratio however

was no help in preventing speed from bleeding off in sustained combat. Paradoxically, this was an advantage that

turned the tables on many an opponent because of the Sabre’s superb low speed

handling, thanks to a fine slatted wing.

An excellent all-round view from the bubble canopy was a delight for the

Sabre pilots. The Sabre’s six 0.5" guns with

a total of 1,800 rounds provided enough firing time to target several aircraft,

as was demonstrated twice in the 1965 War. The Canadair CL-13 Sabre

Mk-6 (designated F-86E in the PAF, not to be confused with the regular North American

Aviation ‘E’ model) was better endowed than the ‘F’ model in terms of

T-W ratio, due to a more powerful engine.  The F-104A Starfighter’s high T-W ratio coupled

with a streamlined supersonic design, positively impacted acceleration, maximum

speed and rate of climb. Due to its sleek profile and fantastic pursuit performance, it came to be known as a 'manned missile.' A good fuel

fraction ensured that it could maintain its high performance long enough. As far as manoeuvrability is concerned, the

Starfighter was an utter disappointment due to the very high wing loading and

low aspect ratio. Armed with a Gatling gun firing

66 rounds a second, along with AIM-9B Sidewinder missiles, the Starfighter generated

enough awe if not a high turn rate, to keep its adversaries at bay!

The F-104A Starfighter’s high T-W ratio coupled

with a streamlined supersonic design, positively impacted acceleration, maximum

speed and rate of climb. Due to its sleek profile and fantastic pursuit performance, it came to be known as a 'manned missile.' A good fuel

fraction ensured that it could maintain its high performance long enough. As far as manoeuvrability is concerned, the

Starfighter was an utter disappointment due to the very high wing loading and

low aspect ratio. Armed with a Gatling gun firing

66 rounds a second, along with AIM-9B Sidewinder missiles, the Starfighter generated

enough awe if not a high turn rate, to keep its adversaries at bay! The Mirage IIIE is a derivative of the earlier

‘C’ model, which was the first Mach 2 fighter from the Dassault stable. It came

to be the progenitor of a very successful series of multi-role fighters that

continue to operate well past their fifth decade since the prototype flight. The

Mirage IIIE has a very low wing loading that is helpful in instantaneous turns,

but an unimpressive T-W ratio robs it of the ability to keep up in a dogfight. A very poor aspect ratio (typical of delta

wing planforms) causes phenomenal drag rise in manoeuvring flight, which is

only worsened by the lack of a tailplane, since the upgoing elevons on the

wings deduct considerably from overall lift. Prolonging a dogfight is thus, sure to be

disastrous. Its Sidewinder missiles, hard

hitting 30-mm cannon, and an airframe customised for high speed are the saving

grace in a hit-and-run fight. The aptly named Mirage can easily go supersonic

at low altitude, and twice over at high altitude.

The Mirage IIIE is a derivative of the earlier

‘C’ model, which was the first Mach 2 fighter from the Dassault stable. It came

to be the progenitor of a very successful series of multi-role fighters that

continue to operate well past their fifth decade since the prototype flight. The

Mirage IIIE has a very low wing loading that is helpful in instantaneous turns,

but an unimpressive T-W ratio robs it of the ability to keep up in a dogfight. A very poor aspect ratio (typical of delta

wing planforms) causes phenomenal drag rise in manoeuvring flight, which is

only worsened by the lack of a tailplane, since the upgoing elevons on the

wings deduct considerably from overall lift. Prolonging a dogfight is thus, sure to be

disastrous. Its Sidewinder missiles, hard

hitting 30-mm cannon, and an airframe customised for high speed are the saving

grace in a hit-and-run fight. The aptly named Mirage can easily go supersonic

at low altitude, and twice over at high altitude. ‘Jew’s Harp’ would not be a misplaced

moniker for the diminutive Gnat, which vied for a place amongst an ensemble of

more daunting fighters. A fine blend of performance and manoeuvrability, it had

a relatively high T-W ratio for a

subsonic fighter, giving it good acceleration, while its low wing loading and

relatively higher aspect ratio conferred it with an impressive turning

ability. Due to its small size, the Gnat

surprised its opponents on many an occasion when it was sighted too late. This

attribute especially, made it a formidable fighter in air combat. The Gnat’s size was, however, also a

liability in so far as it did not permit large external loads, and restricted

it to the role of a 'guns-only' point defence interceptor.

Propensity of its 30-mm cannon to jam was a sore point with pilots, as was claimed

to have happened in combat on more than one occasion. The Gnat had a reasonably good fuel fraction,

which at first sight would appear quite unlikely.

‘Jew’s Harp’ would not be a misplaced

moniker for the diminutive Gnat, which vied for a place amongst an ensemble of

more daunting fighters. A fine blend of performance and manoeuvrability, it had

a relatively high T-W ratio for a

subsonic fighter, giving it good acceleration, while its low wing loading and

relatively higher aspect ratio conferred it with an impressive turning

ability. Due to its small size, the Gnat

surprised its opponents on many an occasion when it was sighted too late. This

attribute especially, made it a formidable fighter in air combat. The Gnat’s size was, however, also a

liability in so far as it did not permit large external loads, and restricted

it to the role of a 'guns-only' point defence interceptor.

Propensity of its 30-mm cannon to jam was a sore point with pilots, as was claimed

to have happened in combat on more than one occasion. The Gnat had a reasonably good fuel fraction,

which at first sight would appear quite unlikely.  India’s first indigenously built jet fighter, the

HF-24 Marut went through serious teething troubles which it failed to outgrow. What

might otherwise have been a first class fighter, it essentially failed to find

a potent powerplant. Poorly endowed with a pair of very low T-W ratio engines,

the HF-24 was useless as an air combat fighter. It was however put to limited

use for ground attack, in which role its four powerful 30-mm cannon packed a

powerful punch.

India’s first indigenously built jet fighter, the

HF-24 Marut went through serious teething troubles which it failed to outgrow. What

might otherwise have been a first class fighter, it essentially failed to find

a potent powerplant. Poorly endowed with a pair of very low T-W ratio engines,

the HF-24 was useless as an air combat fighter. It was however put to limited

use for ground attack, in which role its four powerful 30-mm cannon packed a

powerful punch. The Hunter F-56 was an outstanding fighter in

all respects. Though outdone by the Sabre in manoeuvrability by a slight margin, it made up with its higher speed and better

acceleration. Like the HF-24, its four 30-mm cannon

provided it with tremendous firepower against aerial, as well as ground targets.

The Hunter F-56 was an outstanding fighter in

all respects. Though outdone by the Sabre in manoeuvrability by a slight margin, it made up with its higher speed and better

acceleration. Like the HF-24, its four 30-mm cannon

provided it with tremendous firepower against aerial, as well as ground targets. The MiG-21FL had an uncomplicated 'tailed delta' design,

and was easy to fly even to the limits. It was more manoeuvrable than its

bisonic counterpart, the F-104A, but not in the class of its subsonic

contemporaries whose low wing loadings in particular, were unmatchable. The MiG’s low aspect ratio caused high drag

rise during turns, though a good T-W ratio offset this limitation to quite an

extent. Its K-13 missile, despite

employment restrictions, did instill caution in the minds of adversary pilots;

the 23-mm cannon, however, had low lethality as well as a very short

firing time.

The MiG-21FL had an uncomplicated 'tailed delta' design,

and was easy to fly even to the limits. It was more manoeuvrable than its

bisonic counterpart, the F-104A, but not in the class of its subsonic

contemporaries whose low wing loadings in particular, were unmatchable. The MiG’s low aspect ratio caused high drag

rise during turns, though a good T-W ratio offset this limitation to quite an

extent. Its K-13 missile, despite

employment restrictions, did instill caution in the minds of adversary pilots;

the 23-mm cannon, however, had low lethality as well as a very short

firing time. The Mystère IVA was a reasonably good fighter,

though not as manoeuvrable as the Sabre. It lacked the latter's wing slats, and could not turn as well, especially at low speeds. Except for a few odd aerial engagements,

including a daring duel with an F-104 in the 1965 War, it did not figure

significantly in the fighter role.

The Mystère IVA was a reasonably good fighter,

though not as manoeuvrable as the Sabre. It lacked the latter's wing slats, and could not turn as well, especially at low speeds. Except for a few odd aerial engagements,

including a daring duel with an F-104 in the 1965 War, it did not figure

significantly in the fighter role. With wings swept back at an audacious 62 degrees, the Su-7BMK looked every bit a high-speed fighter-interceptor. However,

its heavily loaded wings were no good for manoeuvrability. Due to a high T-W

ratio, it could rapidly accelerate away, provided it had not run out of three

afterburner light-up chances that were available, which was a serious handicap

in combat. With a poor fuel fraction, staying

in afterburner for long was not a viable prospect anyway. Though endowed with

two hard hitting 30-mm cannon, it could not carry IR missiles, and was best

employed as a ground attack fighter with up to four rocket launchers having 16x57-mm rockets each, as its primary ordnance. Its

robust structure earned it the reputation of being unbreakable, as was

demonstrated in several safe recoveries despite serious battle damage.

With wings swept back at an audacious 62 degrees, the Su-7BMK looked every bit a high-speed fighter-interceptor. However,

its heavily loaded wings were no good for manoeuvrability. Due to a high T-W

ratio, it could rapidly accelerate away, provided it had not run out of three

afterburner light-up chances that were available, which was a serious handicap

in combat. With a poor fuel fraction, staying

in afterburner for long was not a viable prospect anyway. Though endowed with

two hard hitting 30-mm cannon, it could not carry IR missiles, and was best

employed as a ground attack fighter with up to four rocket launchers having 16x57-mm rockets each, as its primary ordnance. Its

robust structure earned it the reputation of being unbreakable, as was

demonstrated in several safe recoveries despite serious battle damage. The aging Vampire FB-52 was not really a match

for the PAF fighters. Its aluminium and

balsa wood structure gave it a very light wing loading, but its poor T-W ratio

and unimpressive maximum speed were grave liabilities, due to which it was

relegated to a second-line role.

The aging Vampire FB-52 was not really a match

for the PAF fighters. Its aluminium and

balsa wood structure gave it a very light wing loading, but its poor T-W ratio

and unimpressive maximum speed were grave liabilities, due to which it was

relegated to a second-line role.Note: Aircraft profiles not to scale.

___________________

> Colour profiles of aircraft, courtesy Tom Cooper.

> PAF aircraft data obtained from respective Pilot's Flight Manual.

> IAF aircraft data obtained from Encyclopedia of World Air Power, edited by Bill Gunston; Hamlyn/Aerospace Publishing Ltd, London, 1981.

© KAISER TUFAIL